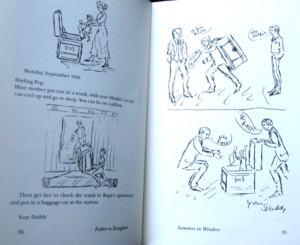

This book is full of Max Perkins’ drawings. Until the last group of letters, written to Bert when she was seventeen, there are drawings, often more than one, on every page. In the summer Max Perkins had to fill up a letter every day. Maybe he used the drawings to fill up some of the space when he ran out of things to say.

Father To Daughter

How Father to Daughter Came About

In 1992 my aunt, Bert Frothingham met a small Boston publisher who convinced her to put together a book of her father’s letters. Her father was Max Perkins, the editor of the famous writers F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, as well as many others. There was already a book of his working letters called Editor To Author.

In 1992 my aunt, Bert Frothingham met a small Boston publisher who convinced her to put together a book of her father’s letters. Her father was Max Perkins, the editor of the famous writers F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, as well as many others. There was already a book of his working letters called Editor To Author.

Max and Ouisie had five daughters. In the summers the family went to Vermont while he stayed in New York to work. When he was away from them, he wrote to one daughter every day in turn.

Bert had all the letters he had written to her, and my mother had all of hers too. Bert’s letters were in a scrapbook her daughter had put together. Mother had made copies of hers before she gave the originals to the Houghton Library at Harvard. Their three sisters, Zippy (Elizabeth), Jane and Nancy were dead by then, but Bert was able to track down some of their letters too.

Bert and I drove from Vermont to Mother’s house on Cape Cod. We spread all the letters and copies out on Mother’s dining room table. They made a huge and daunting mound. We sorted and shuffled through, and gradually we got them into a kind of order, mostly chronological. That was my job, and it took some doing. Some of the letters had no date, and some had only a partial date. We had to figure out a lot of it from what they could remember of what was happening during their summers seventy years before.

After we had the letters organized and had written some connecting pieces, we gave everything to the publisher. He photographed the letters for the book, except for Mother’s letters. The Houghton Library wouldn’t let Mother have her letters back. She had to go there and make a list of the ones she wanted. They hired a very expensive photographer, which she had to pay for. They wouldn’t even let her bring her purse into the room where the letters were. Did they think she would try to steal them back?

The publisher hired a young woman to do the layout and put the book onto the computer. This was when people were just beginning to use computers and desktop publishing. She wanted to learn the business. Anyway, we struggled with her for quite a while. She really couldn’t do it. She kept making us take drawings out because she couldn’t figure out how to place them in the text. And the publisher kept stringing us along. He said the book would be printed in the spring, and then that it would be done in the fall, and then in the spring again. Meanwhile, Bert’s eyes were failing. She was so afraid that she wouldn’t be able to see at all by the time the book was done.

Finally in August 1994, Bert had had enough. We left that publisher. We hired a small press in Windsor, and a designer who knew how to do what we wanted to do, and we did the book ourselves. It was finished in the fall of 1995. I took one of the first copies to Bert. She was almost completely blind by then, but because she knew the book so well, she could see it, or she thought she could. The look on her face was wonderful to see.

We printed 1000 copies the first time. A commercial publisher, Andrews and McMeel made a hardcover version, and later on Bert did a printing of another 1000 to benefit the Windsor Library. There are still copies in secondhand bookstores. You can find them on Amazon.

A few years ago, I took a book apart very carefully and hired a friend of mine to scan it into the computer. We sent the scans to CreateSpace and had a print-on-demand book made. While I was doing that I added a page about my memories of Max, which wasn’t in there before. And at the end, I added a page about The Simple Life and one about Ordinary Magic. I don’t think Max would mind that. You can find the new version on Amazon.