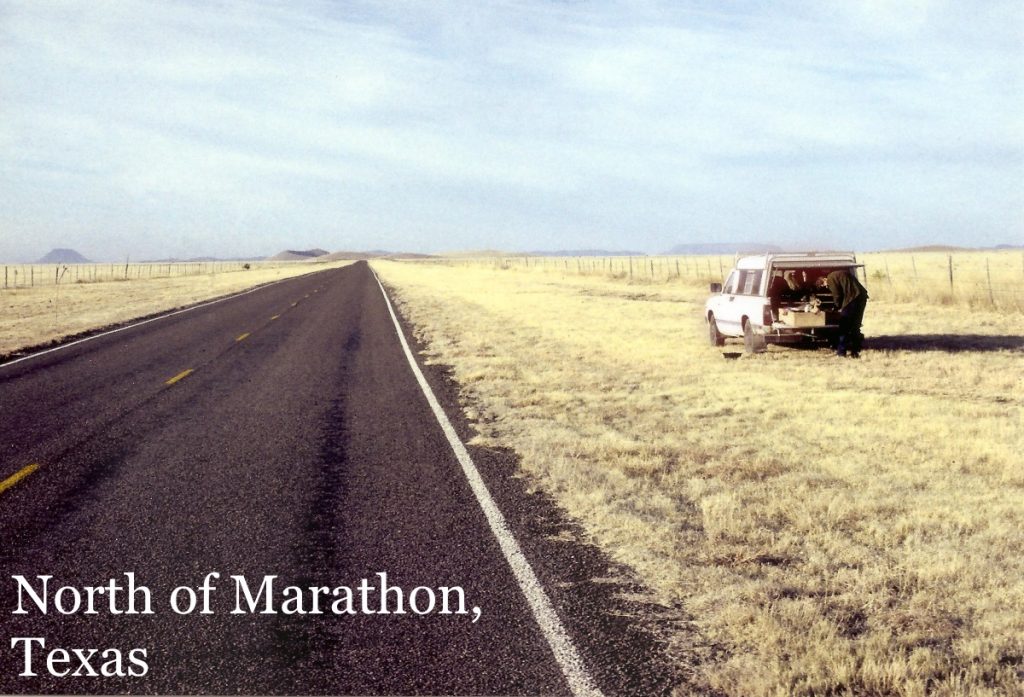

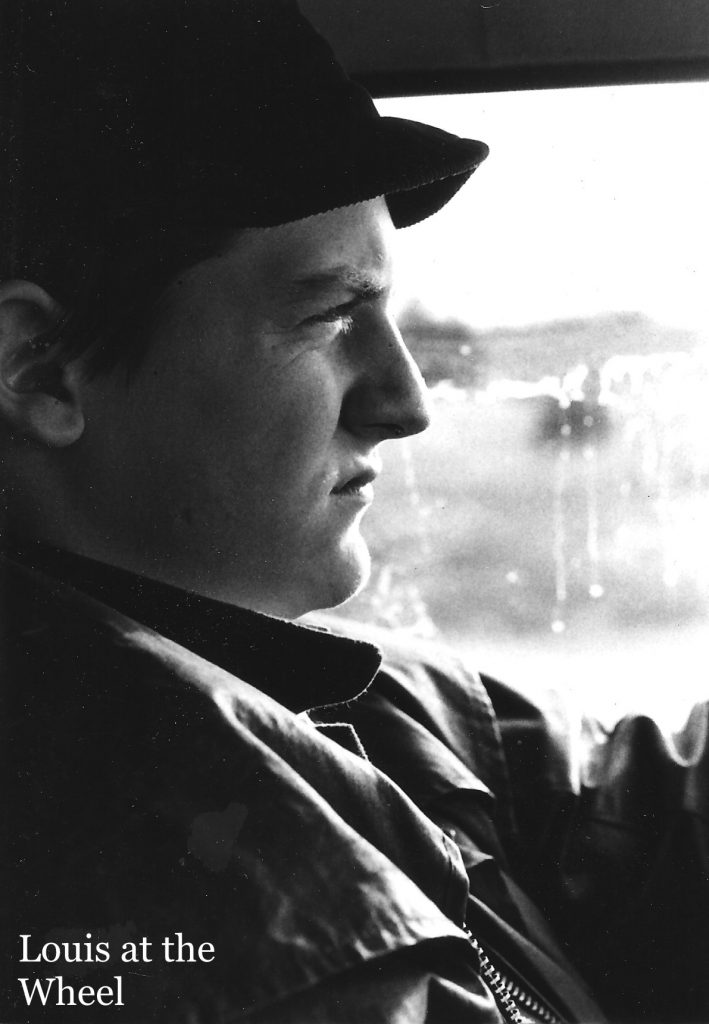

In 1994 two brothers, 10 years apart in age leave rural Vermont and cross the United States in a truck only slightly younger than its passengers. Mutual interest in the American landscape and culture is one of the rare points of agreement as they head south and west taking two months to reach LA. Now, 24 years later, Robby Porter has published the daily journal he kept during their trip. This diary, titled Doodlebug, will evoke thoughts of both “I wish I had done that” and “What were they thinking?” It is an American story involving transgressions against wildlife, Texas politics, bad cooking, home remedies, southern family history, and a friendship almost ruined by falafel.

Pictures from the Book

Read a Sample from Doodlebug

Feb. 8th

I was tremendously depressed as we left New Orleans and I could see no reason and had no energy for continuing the trip. It seemed, frankly, impossible. I persisted feeling this way well past Baton Rouge. Louis was depressed also, although we wisely didn’t talk about it until afterward. We tried to listen to music, but the best tape, Louis’s mixtape with “Tangled Up In Blue” on it, had gotten tangled. He took it apart and tried patiently for about an hour to rewind the tape. He had to do this while we drove over a road with regular bumps, like small frost heaves. Eventually, his patience wore through, well beyond the point where we both knew it was futile. He crushed the tape into little plastic shards, and “Tangled Up In Blue,” “Truckin’,” “Take It Easy,” among others, disappeared for us.

Somewhere beyond Lafayette, the land turned slightly western—that is to say, what the people have done or not done to the land turned slightly western. The farms were set back from the road, there were fields and only a few towns and houses. Also, we could see farther, partly because the interstate was elevated. The sky took on the look of an east Texas sky, ominous clouds above, lime-green fields beneath, but patches of blueness showing through clearly enough so we knew any storm would be swift to come and swift to leave. The vista was reduced to two main elements, open land and sky; for a while, people became an incidental curiosity. Our spirits raised immensely. We entered Texas happy and happy to be there. Only four states from the Pacific Ocean.

************************

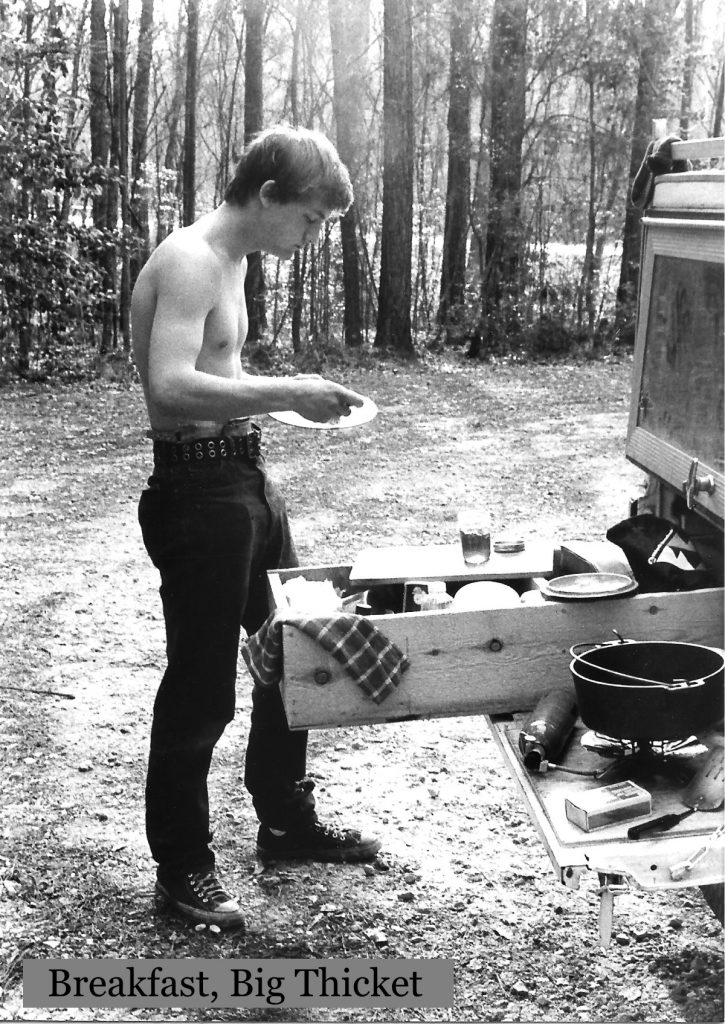

The Big Thicket is a national wilderness preserve, different from a national park in that oil and gas exploration and fishing, and perhaps some hunting, are permitted. We are allowed to camp without paying a fee as long as we sign in and out for hiking, a reasonable solution, and Louis and I feel comfortable here.

We hiked about three miles up Turkey Creek Trail through a variety of trees, pines, magnolias, and occasionally a beech. It is thick here. On the river, Louis saw a large snake slipping from a log into the water and another leaving the bank. It may have been a water moccasin and he may have fulfilled his lifelong obsession with seeing a poisonous snake, but we don’t know. He did spot an anthill on the way back.

“Careful, those might be red ants,” I cautioned.

“Not all red ants sting,” he said, squatting beside it and unsheathing his magnifying glass.

“Careful, don’t stir them up.”

He bent over the hill, trying to get focused on an ant, putting his face and nose dangerously close to them. I watched nervously for signs of a war party advancing up my leg.

“Aha!” Louis said, sitting up and looking at his arm. “Great, I’ve got one on my arm. Yes, it has formic acid.” He squinted at it with the glass.

“Does that mean they can sting?”

He prodded it with his finger. “Yes, there he goes. Have you ever noticed that some ants hunch up when they sting?”

“No, I never noticed that.”

“They bite you and then hunch up because their formic acid is in their last section, so they have to hunch to spray it into the cut.”

“Really?”

“Yup, look at that.” He showed me the sting, slightly swollen and turning red, and he flicked the ant back onto the hill.

“Did you know that in some famous museum, I forget which one, there is a rare species of ant found by an English scientist? He found it while he was having supper with Stalin. It ran across the table, and he recognized it and put it in vodka.”

“That works?” I said.

“The best, strongest alcohol will work. Now, army ants, I would like to see some of those. You know they can kill a deer?”

“No, I didn’t know that. Do they live around here?”

“No, only in the tropics. Some of them are so specialized their jaws are only good for ripping and tearing. They can’t feed themselves without the others.”

************************

It was about 70 degrees and breezy. I typed my journal entry in shirtsleeves.

Louis approached with a flashlight held beside his ear.

“Hey, Robby, wanna see wolf spiders?” I followed him and he shone the light around until he saw some eyes glowing blue. “All right, watch now.”

We walked slowly and, as we got close, I saw a spider with a body about the size of a pea, but it disappeared quickly into its hole. Louis looked around and followed his flashlight beam down to some eyes. “Holy bejesus. That one is a meal in itself,” he said. The spider was about the size of a grape. Its legs probably spanned an inch and three quarters, but it ducked into its hole and we couldn’t prod it out with sticks.

“Do they bite?”

“I think so, but I don’t think they are poisonous.”

I went back to typing by lantern light. A few minutes later, Louis returned to the truck with an insect he had never seen before on a twig. It was about an inch and a half long and had large, grasshopper-style legs, but one was missing. He took it away from a wolf spider that had caught it and let it go, minus a leg, when he approached.

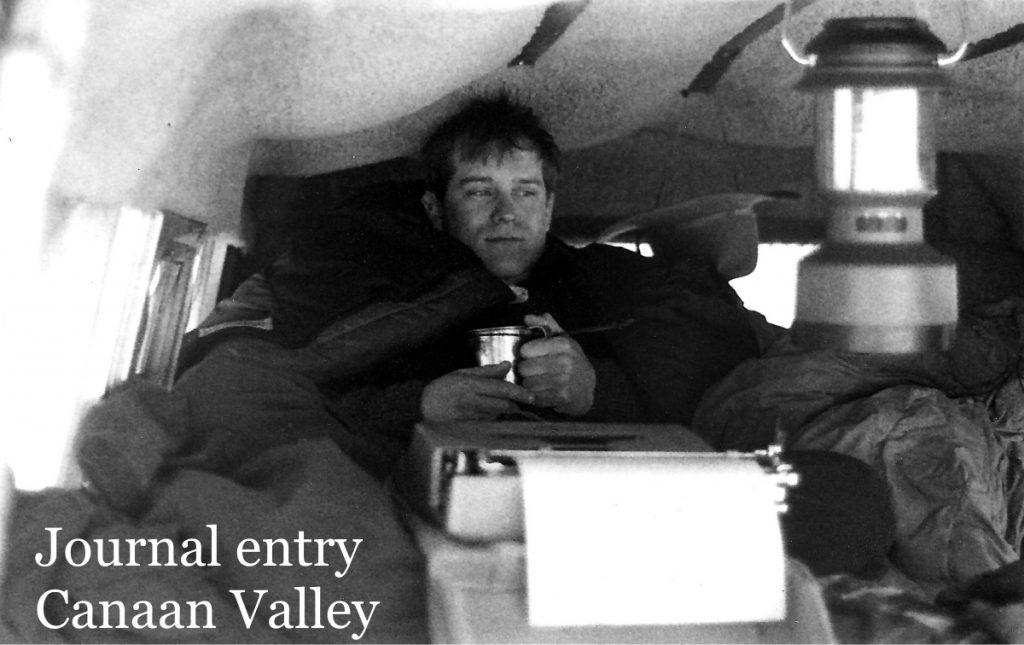

We decided to sleep in the truck instead of camping. This had the advantage of protecting us from ticks, mosquitoes, and snakes and spiders, not to mention ants.